Are church forests the key to biodiversity conservation in Ethiopia?

On Lake Tana, in the highlands of Ethiopia, it is important to protect the cultural and ecological origins of a pristine landscape. The recipe for this could be in the Bible. The area around Lake Tana, in the highlands of northern Ethiopia, now knows many facets of the threat. They range from deforestation of the formerly rich forests to overfishing by a grown industry. But there could be a solution to the problems of the region. And that starts at the water’s edge.

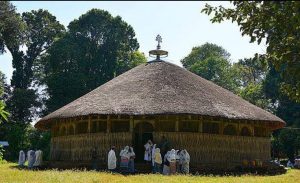

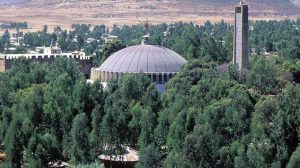

Here are a few up to hundreds of acres of old trees. They are islands of biodiversity and that in a region that has since been largely beaten. The old stocks are called church forests. They are what is left of the original forest of Ethiopia.

The forests are preserved by priests of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church “Tewahedo”, a Christian group that manages these old groves since the 16th century. In Ethiopia, there are still thousands of these groves, which are left in the otherwise barren vegetation. Church followers assume that the church forests must be preserved because they are reserved for God’s creatures. They should be understood as images of the Garden of Eden from the Book of Genesis and must be protected and respected. But it is not good for the woods. When faith and agriculture compete for forests, convenience often wins. A view from the top shows that the church forests are green spots – surrounded by a mosaic of fields, pastures and settlements. It is not surprising that, due to the prolonged drought and conflicts in Ethiopia, planting cereals often takes precedence.

Nevertheless, tree researcher Margaret Lowman and forestry scientist Alemayehu Wassie Esthete want to ensure that future generations of the church forest can still speak in the present tense. To protect what is left of the forest, the duo has teamed up with other like-minded scientists and priests: “We all have the same goal. They call it God’s creatures, we call them biodiversity. But we all want to preserve them, “says Lowman, director of science and sustainability at the California Academy of Sciences.

Lowman met the Ethiopian partner several years ago at a conference on the ecology of the forest in Mexico. According to Lowman, he is one of the few people in the world who deals intensively with church forests. Lowman is affectionately called Canopy Meg, which means treetop Meg. She is one of the leading experts on the forest ecosystem. During her time in Mexico, she learned of the plight of the church forests and the limited resources available to Esthete to continue his research. Lowman started to fight. In 2011, she mobilized a team of scientists to create a catalog of church forests near Lake Tana. This was the first in a series of studies that she was sure could lead to a greater understanding of the importance of church forests. Their work is intended to arouse people’s interest, Lowman hopes.

Fortunately, the flow of information actually gets going. A recent study shows that about 170 indigenous tree and bush species grow in the forests. An encouraging result for a nearly bare region. The groves serve as seed banks for native trees and as a refuge for species that are nowhere else.

Recent research has also suggested that church forests can help local farmers: the forests are a habitat for native bee species and other fertilizing insects that provide an invaluable service to nature. These insects have the potential to increase production yields by up to 40 percent.

Church forests are part of a long tradition of preserving in religious groups, forests and wildlife areas. Shrines, temples and monasteries have been established worldwide as places of refuge, centuries ago, if not millennia. At the moment, according to the Alliance of Religions and Conservation, five to ten percent of rugged regions are owned by religious organizations. Thanks to researchers such as Lowman and Esthete, the value these sacred areas play in preserving the species is becoming increasingly apparent.”Of course we do our best to protect at least some of the church forests from their destruction,” Esthete writes in an e-mail. To this end, the two researchers at the Orthodox Church promote the benefits that environmental monitoring would bring, initiate talks between peasants and priests, and engage scientists in their research.

Both have also launched a pilot project to boost nature conservation. They want to encourage villagers and church elders to build stone fences as boundaries for four church forests so far. This is not an easy task given the amount of work required, coupled with the lack of technical equipment. But the fence construction is worthwhile: farmers acquire land suitable for agriculture. The fences prevent that there are no more interventions in the church forests and also the cattle can no longer penetrate, in order to eat the seedlings. Lowman calls the concept a “win-win-win” project. It motivates peasants and priests alike to keep to the limits of the church area. It takes up, as it were, a winged word: “Good fences make good neighbors.”